some notes on finding each other reborn

I got a call a few nights ago from a friend. Feeling the world is going to hell, and that feeling (thankfully) prompting motivation rather than resignation, he wanted to talk through a few dilemmas at the intersection of his professional and ethical life. Aware that I spent the majority of my life in some sort of relationship with Buddhist practice, he also wanted some guidance on getting his feet wet, there; a sort of foundation for weathering the trials and traumas that come with a commitment to social transformation.

His is, of course, a perfectly intuitive –and increasingly common– journey. Which makes for an occasion to offer a more publicly accessible/useful intervention against the tendency toward spiritual bypass.

Buckle up, kids.

The Dissenter

The truth is that, upon moving to Thailand and experiencing firsthand how Theravada Buddhist institutions have been co-opted by and put in service to the monarchy (with real consequences for people I care about; consequences like prison and death), my relationship with the dhamma effectively ended. At least in the sense of being unable to draw ease or some sense of community from its institutional touchpoints. That said, I am who I am in large part because I spent so much of my life immersed in that literature, practice, etc. That’s not going anywhere. My internal life and how I show up to the world is still largely governed by that, if only for the fact that the proof is in the proverbial pudding – my life and the lives of the people around me benefit enormously from what I onboarded therein.

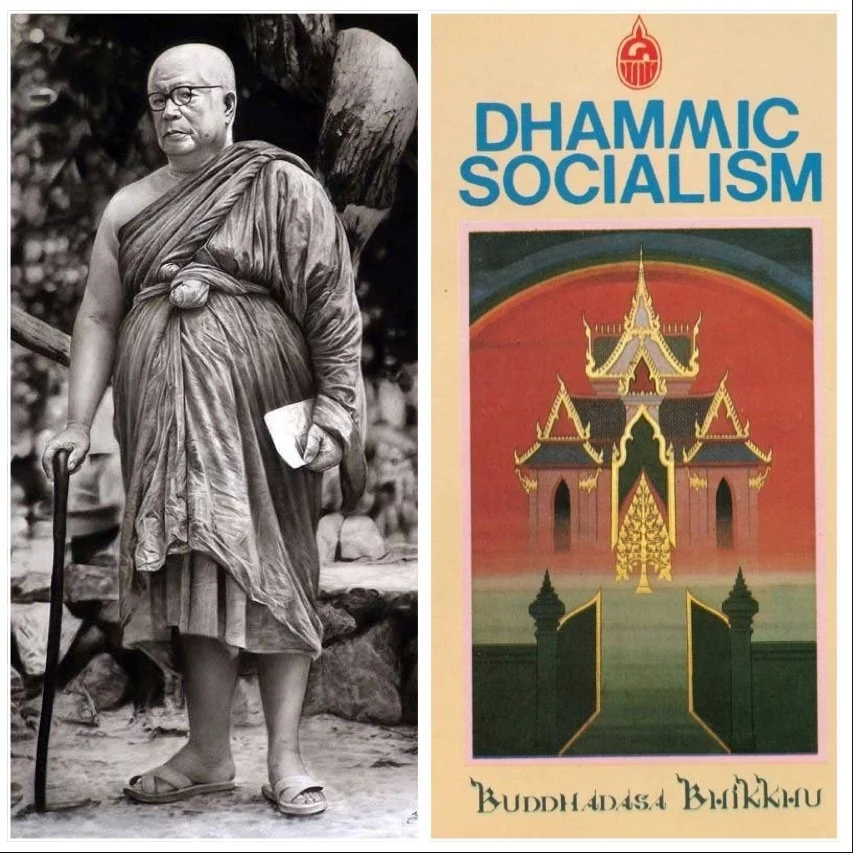

There are notable exceptions to how Thailand has conditioned my relationship with explicitly Buddhist reference points. It’s not all disillusionment. The Thai Forest Tradition that largely informed my own practice is outside the monastic system organized under the monarchy, for example. So my appreciation of it is not sullied by that association. There is also the critical –frankly radical– teaching of Phra Buddhadasa Bhikkhu; a sort of Thai analog to Liberation Theologists in Latin America and the Caribbean. And that’s often at the top of the reading list when friends hit me up looking for points of entry.

Two intertwined, counterintuitive features of Buddhadasa’s legacy offer something incredibly instructive for our moment. First, he firmly rejected the idea that the Buddha taught reincarnation. This will probably come as a shock to most folks reading this. Second, he died of natural causes, and remains one of the most revered Buddhist teachers in the Thai tradition – even at the level of the conservative establishment. This, despite publishing a collection of essays entitled Dhammic Socialism. Which is a gentle way of saying he was not found riddled with bullets a la so many Jesuits in 1980’s Latin America, or more recently exiled Thai dissidents disappeared and dredged from the Mekong with stomachs full of concrete.

Buddhadasa’s rejection of reincarnation was, at its core, an assertion of scriptural integrity. And when I interviewed the Executive Director of his archives five years ago –a guy who’d been a monk alongside the man himself– he explained that this dogged piety to text likely explains his immunity from assassination. Over the years, he faced mafioso-like counsel about staying away from certain topics or assertions, and replied in every case that he was simply citing scripture. This was also, in its own skillful way, an assertion of the tradition’s roots as a rejection of the superstition that entrenched Brahmanic power and caste stratification – the same sorts of systemic gas-lighting, victim-blaming, and manipulation widespread not just in Thailand, but in late-capitalism broadly.

Context is Everything

Let’s get down to brass tacks: The historical Buddha was fiercely pragmatic, and made precious few ontological claims in his life. He was interested in suffering, its causes, and getting free of it – and not much else. The suttas are actually rife with accounts of him waving off and refusing to answer all manner of questions on the grounds that their premises were irrelevant to his project, uninteresting to him, or “imponderable”. This included the preoccupations of pretty much every spiritual tradition in the world. How did the universe begin? Not interesting or actionable. Next question.

And while one can find references to rebirth in the suttas, it’s critical to remember two things:

First, they were recorded in Pāli; a creole of Sanskrit with no written form. There’s a lot worth unpacking there, but for our purposes, it’s enough to note that we’re talking about a time in which literacy was incredibly rare, and mostly concentrated among the powerful. It took roughly 250 years for the teachings of the historical Buddha to be written down. Prior to that, they’d been committed to memory and passed down through enumeration and chanted verse. In that time, the monastics in charge of that oral tradition were dependent on patronage from a series of monarchs whose loyalties to Brahamanic power waxed and waned. It’s common sense to assume modifications to scripture occurred here and there, if only as concessions to ensure the survival of the Buddha’s following.

Additionally, instruction has different contours when you take literacy out of the equation. Vygotsky’s zone of proximal development in educational psychology applies here; people progress differently on learning journeys based on what they already know or understand. The historical Buddha absolutely knew this, inasmuch as he wielded it like a Swiss army knife. The very terms one comes across in even the most cursory engagement with the tradition – dukkha and nibbana (aka nirvana)-- refer to an axel’s misalignment with a wheel and the point at which a dish has finished cooking and can be taken off the flame (respectively). Vocabulary and stories from the Vedas were common to most of his audiences, as were fire-worship and other ascetic traditions. He leveraged all of these in his sermons.

Second, the historical Buddha laid out three universal claims about the world; what he called the Three Marks of Existence. These are not a footnote. They are arguably the pillars on which the entirety of his teaching rests, and the thread one can observe running through it all. They are: Impermanence, lack of a stable essence, and dissatisfaction. In short, all things change. All things being in a state of flux, they cannot retain essential qualities or identity. In turn, they are bound to disappoint us because their changing is indifferent to our needs and expectations.

Take a look around, see if you can find a case in which this is not true. Good luck. Your friends, your possessions, your passions, your family, your career, your city, your body. All of these are constantly changing, none of them have any fixed identity that survives those changes, and we have all lamented both those changes and that lack of stability.

It’s a rather apt illustration of the Buddha’s insistence that we not believe anything we cannot directly experience – even if he taught it. The keys to the liberation Corvette aren’t external to us; they’re right here in our moment to moment experience. You don’t need amulets or rituals or numerology or creation myths or clerics or gurus. It’s all right there in the fact that your dog’s gonna die and your knees are gonna go.

All Self is Drag

So, how then reincarnation; the transmigration of a permanent soul or essence across lifetimes and bodies? The short answer is – it’s a superstition like any other; incompatible with the world as the historical Buddha observed it. There’s, quite literally, a conversation in the suttas where the Buddha challenges his closest attendant to provide any account of god or the afterlife that isn’t reducible to a fear of dying (spoiler: his attendant comes up empty-handed). Scroll back to the note about what was and wasn’t relevant to the Buddha’s project.

Q: What happens when any of us dies? A: Who cares?

And if we take the Three Marks of Existence seriously – what “us”, anyway? What we understand as selves are more or less interchangeable with personalities, and those aren’t strictly conditioned by death. Relationships, traumas, addictions, learning – all routinely make entirely new people of us. The unvarnished reality of our “selves” is that they are, above all else, incredibly contingent and fragile. Forget that we all grow and change; the exit of any one of us from the lives of those who recognize us is always just a head injury or Alzheimer’s-onset away.

Nevermind that each of us is socially constituted. In the opening chapter of Undoing Gender, Judith Butler illustrates this beautifully, reflecting on the lives of queer people who survived the worst of the AIDS crisis, and how mourning functioned therein. Each of us, as a self that we can identify and describe, is the product of engagements; of bouncing signals off a constellation of surfaces, moment to moment. People, animals, spaces, routines. When someone or something is abruptly removed from that constellation, it’s not just that some external piece of our experience has gone missing; it’s that the arrangement of those signals bouncing back at us –the signals that tell us who we are, that make us who we are– has changed. We have been changed.

In Butler’s account, mourning is not so much an experience of sudden or lingering lack. It’s the disorientation of finding ourselves remade, against our will; the helplessness of inhabiting a self we don’t recognize; one indifferent to our reliance on a version that no longer exists. There’s an adjustment period, there. A learning curve. It’s messy, non-linear, confusing, painful. We do not exist as islands. We make and unmake each other.

“Truth” is a Product of Power

A certain process of elimination arises, here. After all, the vocabulary of reincarnation absolutely exists. And it has persisted for enough of human history to suggest some functional utility. How do we explain that? A quick stroll through Vol. 1 of Michel Foucault’s History of Sexuality offers that a bit of guidance. Foucault’s thesis was that sex as a discreet category or act does not exist. If you’re having trouble with that, swap in virginity, then ask yourself what act undoes virginity; then imagine people who might never engage in that act, but who you would reasonably perceive as sexually active (ie, if vaginal penetration does the trick, are gay men virgins? If just penetration, are lesbians who do not engage in it virgins?). Lather, rinse, repeat. In short order, you realize that categories like sex and virginity don’t actually describe a discreet thing that exists out in the world.

Foucault posited, instead, thinking about the matter in terms of bodies and pleasures. But the concepts and vocab of sex (and virginity) still very much came into being and continue to hold central place in our lives. If not to describe something actual, then to what end? Foucault argued these concepts allow for the exercise of particular forms of power. For his purposes, this was bound up with the power of confession – an historical turn from confessing our acts to priests, to confessing our fleeting thoughts, desires, and impulses as though they tell some disproportionate truth about who we are. This is, in effect, the core of the coming-out process; the distinction between homosexual acts (bodies and pleasures) and homsexual identity (a statement not of what we do, but who we are; an effect of heteronormative othering). In other words, sex as a concept exists so that certain people can tell us who we are, and to ensure that we believe them.

So, if reincarnation has no basis in a reality that can be directly experienced (remember, this was fundamental for the historical Buddha) and is, in fact, at odds with the principles that govern our moment to moment lives – what function does its vocabulary perform? If you guessed the exercise of power, give yourself a high-five. You just landed on the very origins of the Buddha’s project: A rebellion against and rejection of the superstitions and rituals by which Brahamans marshaled and exploited masses of subjects.

If you’re poor, or sick, or homeless, or abused – you’ve no need of an institutional analysis that could yield radical transformation, so long as you believe it’s your karma; that some misdeed or misstep in some past life has made you deserving of what you endure. Further, this framing of experience tells you that you can achieve escape velocity from those conditions by committing yourself to a behavioral program prescribed by the very same people who told you it’s all your fault to begin with.

Sound familiar? Caste. Prosperity gospel. Conversion therapy. Respectability politics. Neoliberal ideology and hustle culture. Marayaat and Thai-ness.

Buddhadasa Bhikkhu wasn’t just being a stickler about scripture. He was attempting to re-center the radically liberatory core of the historical Buddha’s project; to decondition Thai audiences; to give them permission to disbelieve that they deserved the horrors of absolute monarchy or the colonial regimes by which it was surrounded; the ethno-nationalist politics that came in its wake; the concentrations of wealth that intensified once the US began devastating the region, abetted by the Thai political and military elite. It was surely no accident that the forest monastery he founded in the southern Thai province of Surat Thani was named Suan Mokkh - “The Garden of Liberation”.

Fanon in the Cosmological Ointment

It’s one thing to name the tools for that psychological decolonization, as a sort of instruction in defense against outside forces. It’s another to name the game in a nod toward going on offense. Notably, the historical Buddha did just that, as well. Albeit, subtly. It is perhaps most manifest in what’s been fiercely recast as pacifying superstition: The Planes of Existence, predictably reduced to “Buddhist cosmology” with due haste.

Across the Pāli Canon, one finds references to as many as thirty-one planes of existence. These are subdivided variously, but the most conventional description organizes them as heavenly, worldly, and hellish. And no shortage of column space has been devoted to recuperating them as cousins to the celestial reward/punishment scaffolding of the world’s major religions. Only, they’re quite clearly not.

For starters, these references are non-binary. We’re not talking about Heaven and Hell; we’re talking about containers a full fifteen times as numerous. Moreover (points awarded if you notice a theme, here), they’re impermanent. More still, they’re lateral and non-sequential; one can move from any one to any other.

If we know that the historical Buddha’s teachings fundamentally rejected any kind of stable essence or self that might transmigrate between these planes, and we similarly know that teachers like Buddhadasa went out on a limb to emphasize this – we’re left with how to square a cosmology that suggests otherwise. One approach is the modern deus ex machina of late secular Buddhist scholars: Arguing that the references to these planes of existence reflect canonical contamination; that these are the residue of Vedic thought dropped into Pāli scripture during its oral transmission. While that residue absolutely exists, and that’s absolutely a thing that happened, I find that explanation unconvincing. Worse, I find it uninstructive.

Here’s why: When the descriptions of these planes are ordered on a spectrum of (for want of better terminology) “worst” to “best”, they bear an uncanny resemblance to Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. That is – heavenly, worldly, and hellish begin to look an awful lot like descriptions of experience within a world where power and resources are so concentrated at one end that beings pass their days in blissful hallucination, while below some manage to get by and maybe even access joy or refinement – all sitting atop scenes of horrific deprivation and suffering. In effect, samsara starts to look a lot less like the universe-building of fantasy novels, mashed up with Hindu morality, and instead resembles a constellation of psychological states delivered with a pedagogical strategy tailored for an audience of a very particular time and very particular literacy.

That we read nibbana as enlightenment, and not as metaphor drawn from culinary vernacular; or moksha as liberation, as though it was not also the word for orgasm, while reading these planes of existence as literal – is a choice. A choice not to see power, privilege, and exploitation. A choice not to see abuse, starvation, and addiction. A choice, instead, to see some cosmic system of reward and punishment per some mysterious unmoving standard of behavior in a world observable only in its constant movement.

It’s worth asking who made those choices and why. The historical Buddha certainly did. When asked, on his deathbed, to whom he would designate the authority to succeed him as teacher, he informed monks there would be no succession. Rather, he instructed them, “be lights unto yourselves”.

Of particular note in this dubious “cosmology” is that ethics retain in only one of its thirty-one realms. That is to say, it is only possible to practice the Buddha’s ethical teaching –and by extension, to achieve liberation– in one of those: The human realm. We can no more impose ethics of nonviolence or honesty on the deprived, starving, exploited, and afflicted than we can expect either from those intoxicated by power and excess.

Liberation, in aggregate, is a matter of bringing everyone to human conditions, where they have the stability and mobility to make meaningful, measured decisions about their lives.

We are all increasingly being crowded into the hellish end of that spectrum. Into states of deprivation.

We get one physical body with which to do this. Eyes on the prize.